Merkle trees are a fundamental part of what makes blockchains tick. Although it is definitely theoretically possible to make a blockchain without Merkle trees, simply by creating giant block headers that directly contain every transaction, doing so poses large scalability challenges that arguably puts the ability to trustlessly use blockchains out of the reach of all but the most powerful computers in the long term. Thanks to Merkle trees, it is possible to build Ethereum nodes that run on all computers and laptops large and small, smart phones, and even internet of things devices such as those that will be produced by Slock.it. So how exactly do these Merkle trees work, and what value do they provide, both now and in the future?

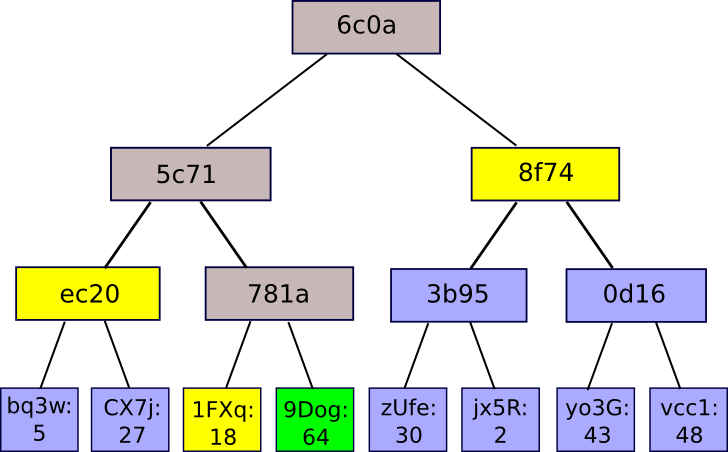

First, the basics. A Merkle tree, in the most general sense, is a way of hashing a large number of “chunks” of data together which relies on splitting the chunks into buckets, where each bucket contains only a few chunks, then taking the hash of each bucket and repeating the same process, continuing to do so until the total number of hashes remaining becomes only one: the root hash.

The most common and simple form of Merkle tree is the binary Mekle tree, where a bucket always consists of two adjacent chunks or hashes; it can be depicted as follows:

So what is the benefit of this strange kind of hashing algorithm? Why not just concatenate all the chunks together into a single big chunk and use a regular hashing algorithm on that? The answer is that it allows for a neat mechanism known as Merkle proofs:

A Merkle proof consists of a chunk, the root hash of the tree, and the “branch” consisting of all of the hashes going up along the path from the chunk to the root. Someone reading the proof can verify that the hashing, at least for that branch, is consistent going all the way up the tree, and therefore that the given chunk actually is at that position in the tree. The application is simple: suppose that there is a large database, and that the entire contents of the database are stored in a Merkle tree where the root of the Merkle tree is publicly known and trusted (eg. it was digitally signed by enough trusted parties, or there is a lot of proof of work on it). Then, a user who wants to do a key-value lookup on the database (eg. “tell me the object in position 85273”) can ask for a Merkle proof, and upon receiving the proof verify that it is correct, and therefore that the value received actually is at position 85273 in the database with that particular root. It allows a mechanism for authenticating a small amount of data, like a hash, to be extended to also authenticate large databases of potentially unbounded size.

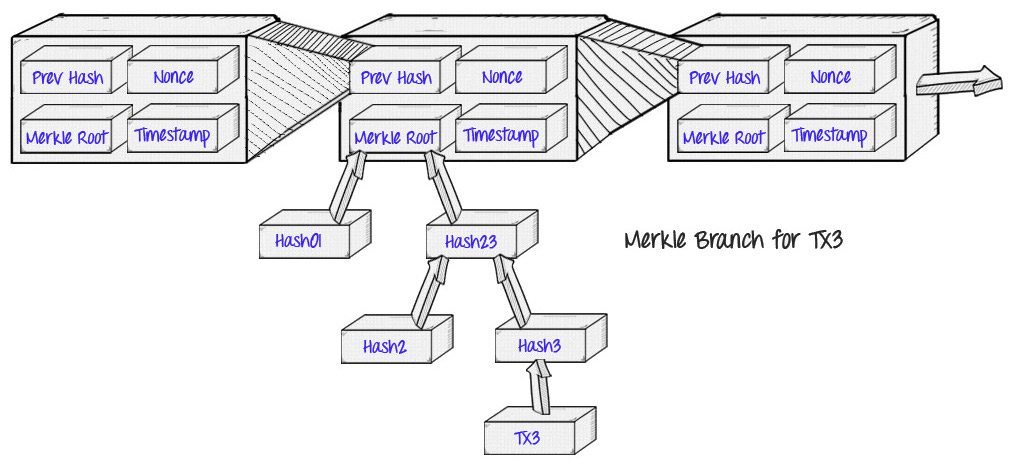

Merkle Proofs in Bitcoin

The original application of Merkle proofs was in Bitcoin, as described and created by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2009. The Bitcoin blockchain uses Merkle proofs in order to store the transactions in every block:

The benefit that this provides is the concept that Satoshi described as “simplified payment verification”: instead of downloading every transaction and every block, a “light client” can only download the chain of block headers, 80-byte chunks of data for each block that contain only five things:

- A hash of the previous header

- A timestamp

- A mining difficulty value

- A proof of work nonce

- A root hash for the Merkle tree containing the transactions for that block.

If the light client wants to determine the status of a transaction, it can simply ask for a Merkle proof showing that a particular transaction is in one of the Merkle trees whose root is in a block header for the main chain.

This gets us pretty far, but Bitcoin-style light clients do have their limitations. One particular limitation is that, while they can prove the inclusion of transactions, they cannot prove anything about the current state (eg. digital asset holdings, name registrations, the status of financial contracts, etc). How many bitcoins do you have right now? A Bitcoin light client can use a protocol involving querying multiple nodes and trusting that at least one of them will notify you of any particular transaction spending from your addresses, and this will get you quite far for that use case, but for other more complex applications it isn’t nearly enough; the precise nature of the effect of a transaction can depend on the effect of several previous transactions, which themselves depend on previous transactions, and so ultimately you would have to authenticate every single transaction in the entire chain. To get around this, Ethereum takes the Merkle tree concept one step further.

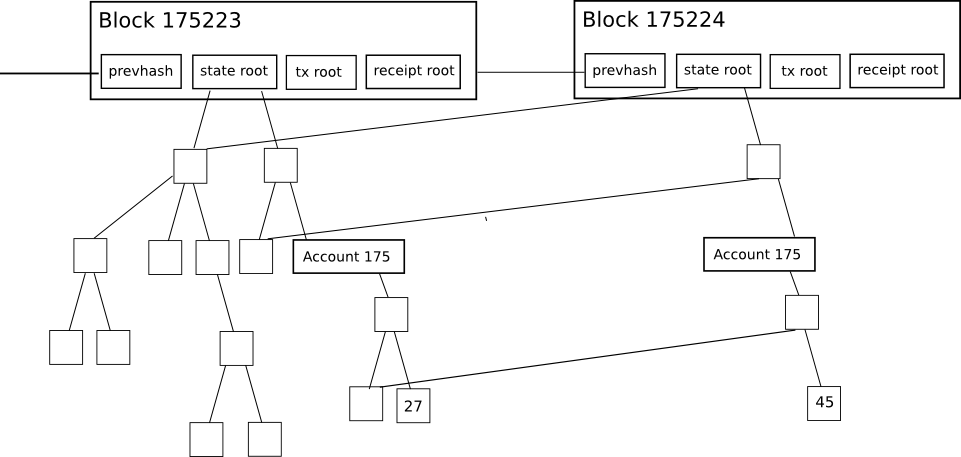

Merkle Proofs in Ethereum

Every block header in Ethereum contains not just one Merkle tree, but three trees for three kinds of objects:

- Transactions

- Receipts (essentially, pieces of data showing the effect of each transaction)

- State

This allows for a highly advanced light client protocol that allows light clients to easily make and get verifiable answers to many kinds of queries:

- Has this transaction been included in a particular block?

- Tell me all instances of an event of type X (eg. a crowdfunding contract reaching its goal) emitted by this address in the past 30 days

- What is the current balance of my account?

- Does this account exist?

- Pretend to run this transaction on this contract. What would the output be?

The first is handled by the transaction tree; the third and fourth are handled by the state tree, and the second by the receipt tree. The first four are fairly straightforward to compute; the server simply finds the object, fetches the Merkle branch (the list of hashes going up from the object to the tree root) and replies back to the light client with the branch.

The fifth is also handled by the state tree, but the way that it is computed is more complex. Here, we need to construct what can be called a Merkle state transition proof. Essentially, it is a proof which make the claim “if you run transaction T on the state with root S, the result will be a state with root S’, with log L and output O” (“output” exists as a concept in Ethereum because every transaction is a function call; it is not theoretically necessary).

To compute the proof, the server locally creates a fake block, sets the state to S, and pretends to be a light client while applying the transaction. That is, if the process of applying the transaction requires the client to determine the balance of an account, the light client makes a balance query. If the light client needs to check a particular item in the storage of a particular contract, the light client makes a query for that, and so on. The server “responds” to all of its own queries correctly, but keeps track of all the data that it sends back. The server then sends the client the combined data from all of these requests as a proof. The client then undertakes the exact same procedure, but using the provided proof as its database; if its result is the same as what the server claims, then the client accepts the proof.

Patricia Trees

It was mentioned above that the simplest kind of Merkle tree is the binary Merkle tree; however, the trees used in Ethereum are more complex – this is the “Merkle Patricia tree” that you hear about in our documentation. This article won’t go into the detailed specification; that is best done by this article and this one, though I will discuss the basic reasoning.

Binary Merkle trees are very good data structures for authenticating information that is in a “list” format; essentially, a series of chunks one after the other. For transaction trees, they are also good because it does not matter how much time it takes to edit a tree once it’s created, as the tree is created once and then forever frozen solid.

For the state tree, however, the situation is more complex. The state in Ethereum essentially consists of a key-value map, where the keys are addresses and the values are account declarations, listing the balance, nonce, code and storage for each account (where the storage is itself a tree). For example, the Morden testnet genesis state looks as follows:

{

"0000000000000000000000000000000000000001": {

"balance": "1"

},

"0000000000000000000000000000000000000002": {

"balance": "1"

},

"0000000000000000000000000000000000000003": {

"balance": "1"

},

"0000000000000000000000000000000000000004": {

"balance": "1"

},

"102e61f5d8f9bc71d0ad4a084df4e65e05ce0e1c": {

"balance": "1606938044258990275541962092341162602522202993782792835301376"

}

}

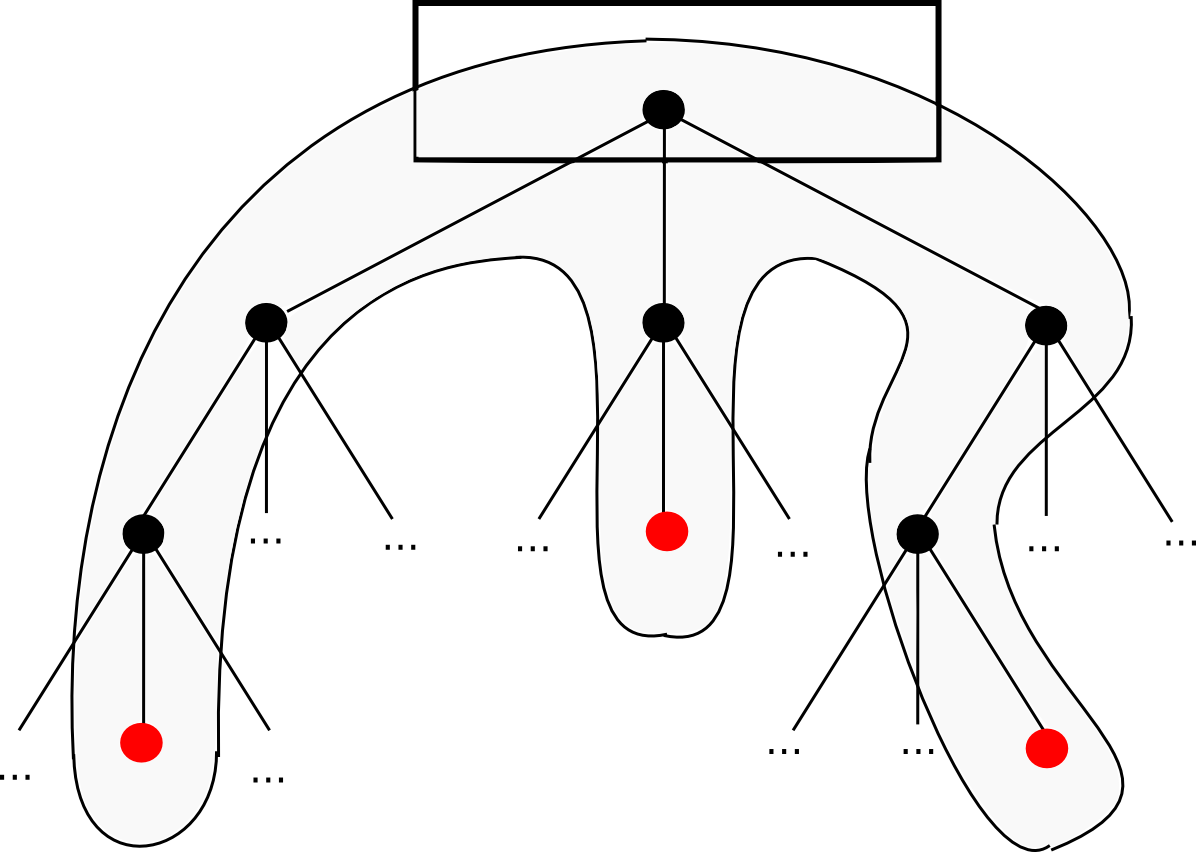

Unlike transaction history, however, the state needs to be frequently updated: the balance and nonce of accounts is often changed, and what’s more, new accounts are frequently inserted, and keys in storage are frequently inserted and deleted. What is thus desired is a data structure where we can quickly calculate the new tree root after an insert, update edit or delete operation, without recomputing the entire tree. There are also two highly desirable secondary properties:

- The depth of the tree is bounded, even given an attacker that is deliberately crafting transactions to make the tree as deep as possible. Otherwise, an attacker could perform a denial of service attack by manipulating the tree to be so deep that each individual update becomes extremely slow.

- The root of the tree depends only on the data, not on the order in which updates are made. Making updates in a different order and even recomputing the tree from scratch should not change the root.

The Patricia tree, in simple terms, is perhaps the closest that we can come to achieving all of these properties simultaneously. The simplest explanation for how it works is that the key under which a value is stored is encoded into the “path” that you have to take down the tree. Each node has 16 children, so the path is determined by hex encoding: for example, the key dog hex encoded is 6 4 6 15 6 7, so you would start with the root, go down the 6th child, then the fourth, and so forth until you reach the end. In practice, there are a few extra optimizations that we can make to make the process much more efficient when the tree is sparse, but that is the basic principle. The two articles mentioned above describe all of the features in much more detail.

Leave a Reply