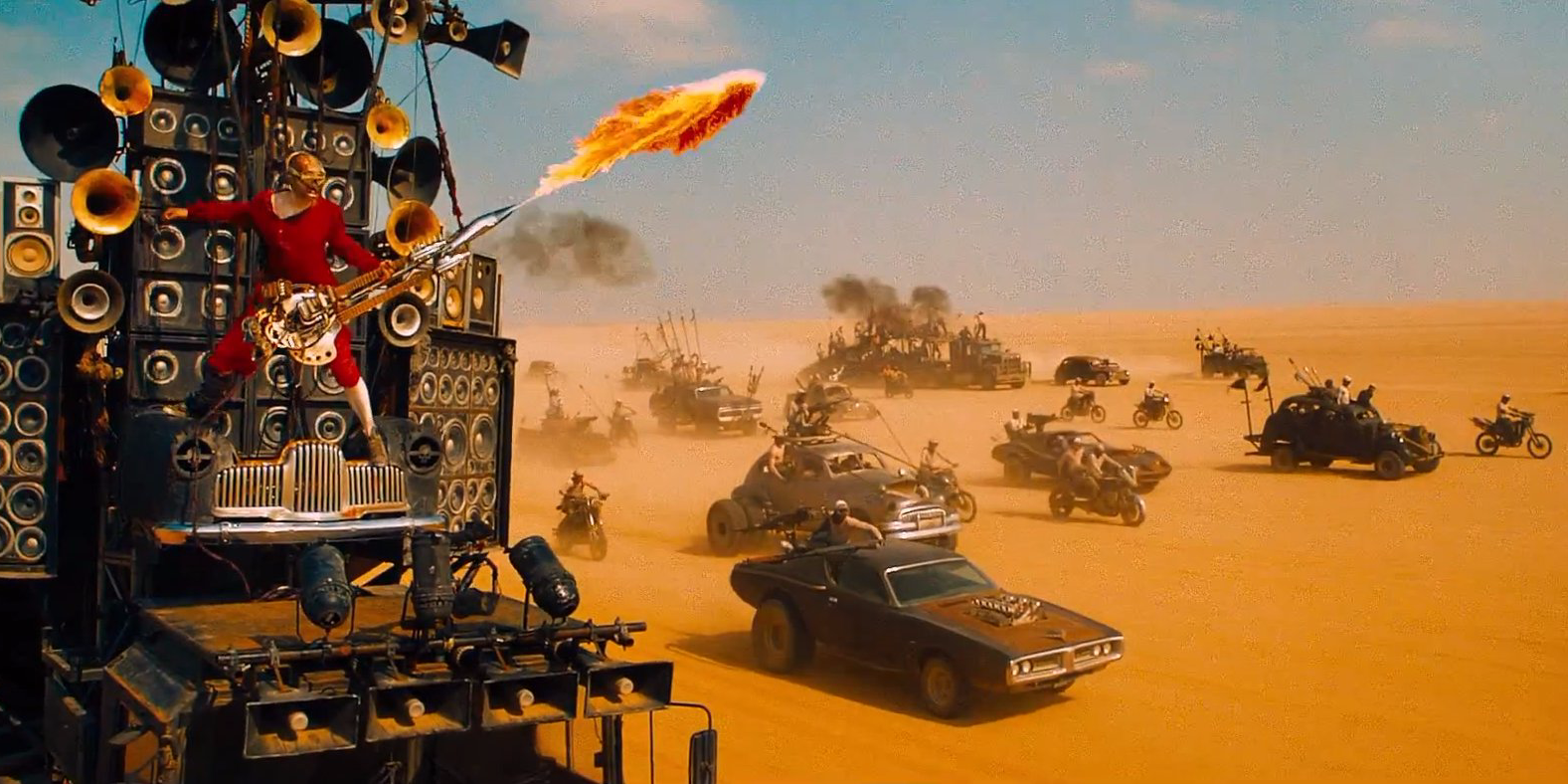

I’ve been thinking recently about post-apocalyptic wastelands. Specifically, about this scene from Mad Max: Fury Road, when the main characters have just escaped the first wave of pursuit, and are staying ahead of their would-be captors. They need to keep moving, but still need to do maintenance on the centerpiece of the movie: a gigantic “war rig” truck driving them to safety. So Charlize Theron climbs out under the cab to make some repairs en-route:

The idea of conducting repairs on a big complicated truck while it’s still moving is just so appropriate for the film’s high-octane drama. It occurred to me while I was watching that this situation is an apt metaphor for the EIP process and the work of the core devs.

Changes to the Ethereum protocol happen LIVE, and a lot of careful, complex engineering goes into crafting upgrades so that everything, and everyone (if possible) keeps rolling along. There are still bumps on the road out in the blockchain badlands, but by and large Ethereum remains well ahead of any other marauding vehicles (technical debt) — so long as the rig keeps pace and doesn’t stop moving toward the horizon. New proposals have the potential to be a little disruptive in the short term to the status quo, but are usually valuable improvements overall to the protocol.

The upgrade I want to discuss today fits into the category of “Ethereum 1.x”, but it’s not part of the Stateless Ethereum effort: A new gas fee market / block size mechanism. The proposal has become a really interesting case study in community and developer feedback for Ethereum improvement. By looking at how this EIP has changed over time with more developer discussion, I think we can learn a lot about constructive discussion in Ethereum development, and hopefully have some clear insights (or at the very least, vague aphorisms) to help guide the discussion on significant changes further out from the Stateless Ethereum initiative.

Ordinarily in this series I try to be very methodical and ‘into the weeds’, but in this instance I want to put more emphasis on the content and character of the discussion surrounding the proposals, rather than the technical minutia contained within. But we have to have some idea of what we’re talking about here, so let’s look very briefly at what EIP-1559 and ‘Escalator’ propose before going “meta” and considering how the discussion has progressed and where it’s at today.

EIP 1559

The motivations for the original EIP 1559 are a good place to start, and they’re fairly straightforward:

The current “first price auction” fee model in Ethereum is inefficient and needlessly costly to users. This EIP proposes a way to replace this with a mechanism that adjusts a base network fee based on network demand, creating better fee price efficiency and reducing the complexity of client software needed to avoid paying unnecessarily high fees.

In the current system, newly submitted transactions must wait to be included in the next block by a miner, but they can incentivize miners to include their transaction by increasing the gasPrice parameter higher than the network average. Miners, if they are being rational, will always be looking to fill new blocks with transactions that maximize their payout, and thus the transactions included first in the next block can be always expected to be the ones with the highest gas price.

The trouble with this first price auction model is that things can get out of hand quickly in times of high demand. When blocks are close to full, the cost of getting a transaction included in the next block can spike dramatically as users try to out-bid each other for inclusion. Even though currently miners have some ability to increase the number of transactions included in a single block, that limit can’t change very quickly and realistically miners are happy to capitalize on small full blocks rather than push the block gas limit up higher (larger blocks are, because of Uncle rates, a more risky proposition for a miner). Especially if your wallet is using pricing algorithms to target inclusion within a specified time frame (read: provide a good ordinary user experience), you might end up paying pretty ridiculous fees to get your transaction into a (nearly) full next block.

EIP 1559 introduces the concept of a ‘base fee’ in gas that is set to dynamically adjust so that the overall gas usage in a block moves toward the current limit of 10 million gas. Rather than going into the pockets of miners, the base fee is burned. To provide incentive for inclusion, users specify a ‘tip’ parameter, together with the maximum amount they are willing to pay for the transaction to be included in a block, and miners keep the tip.

Because the base fee does not fluctuate wildly at the whim of instantaneous network demand, users are somewhat insulated from the inefficiencies of a first price auction model (the ‘tip’ remains first-price), and because the base fee is burned rather than given to the miners, there is no incentive for miners to try and manipulate the fee. Importantly, the mechanism also attempts to solve a big problem for wallet developers automatically trying to estimate network fees by making them much more predictable.

There are several places to read more about EIP 1559; I would recommend Vitalik’s EIP1559 FAQ and Barnabe’s Jupyter notebook if you want to go deeper.

A new challenger approaches: Escalator

Inefficiency of the current first price auction system for Ethereum fees is not controversial, and it’s important to point this out explicitly: No one disputes that the current fee mechanism could be better, and finding an alternative to the first price auction would be indisputably good for Ethereum as a whole — at the end of the day it’ll make things better for both developers and end users alike. We all can and should agree on this.

The new mechanism proposed in EIP 1559 is, however, just different from the way it’s done right now, and changing it will cause some problems, in particular with any software that builds and submits Ethereum transactions for users. Wallets in particular will need to make significant changes to accommodate the new mechanism. Even if things eventually become better for everyone in the long run, in the short term it puts a big burden on the developers working to adjust to the change and prevent their software from breaking.

After EIP 1559 had been floating out in the primordial soup for a while, the community started to weigh in, including wallet developers who would be most affected by the changes proposed. Rather than resist the EIP, wallet developers took an interesting route of discussion. They reconsidered the core motivations for the EIP (improving the UX of Ethereum transactions), and put the EIP into that context, essentially saying “If we’re going to be doing all this work anyways we should from the very beginning have an idea of what it’s going to look like to a user, and we should use that to help guide what’s being proposed”.

This is the over-simplified story behind Dan Finlay’s counter-proposal to EIP 1559: The Escalator Algorithm. It’s similar in a lot of ways to the mechanism of 1559, and has nearly identical motivations and goals. Escalator is presented to stand in as an alternative improvement proposal which allows for a much more nuanced discussion of either mechanism presented in isolation.

To facilitate a more productive and concrete discussion about the gas fee market, I felt it was important to present an alternative that is clearly superior to the status quo, so that any claimed properties of EIP-1559 can be compared to a plausible alternative improvement.

The Escalator mechanism is similar to the current single price auction model, with a few important changes:

- Rather than submitting a transaction with a fixed bid, users submit aptly-named ‘escalating’ bids and specify a maximum amount they are willing to pay to get the transaction included. All bids are put into a queue of ‘escalators’ that gradually and predictably increase all bids in queue at the same rate. This provides a good mechanism for price discovery that still allows users to tweak their settings based on how urgently they want a transaction included, and how much they are willing to pay for it.

The main advantage for escalator is that it enables highly efficient price discovery, while at the same time protecting users from over-paying by charging the second price in queue. It has some of the same strengths as 1559 as well, making it easier for users to choose the right fee, even in times of network congestion. Notably, the escalator by itself would not make any changes to the mechanisms that determine block size.

The “Escalator Algorithm” proposal is interesting in its own right, and I highly recommend reading the ‘user strategy’ section to get a good high-level comparison of the 3 different models of transaction processing. If you like this kind of thing, the paper that introduces the escalator algorithm is also well worth digging into, but I digress…

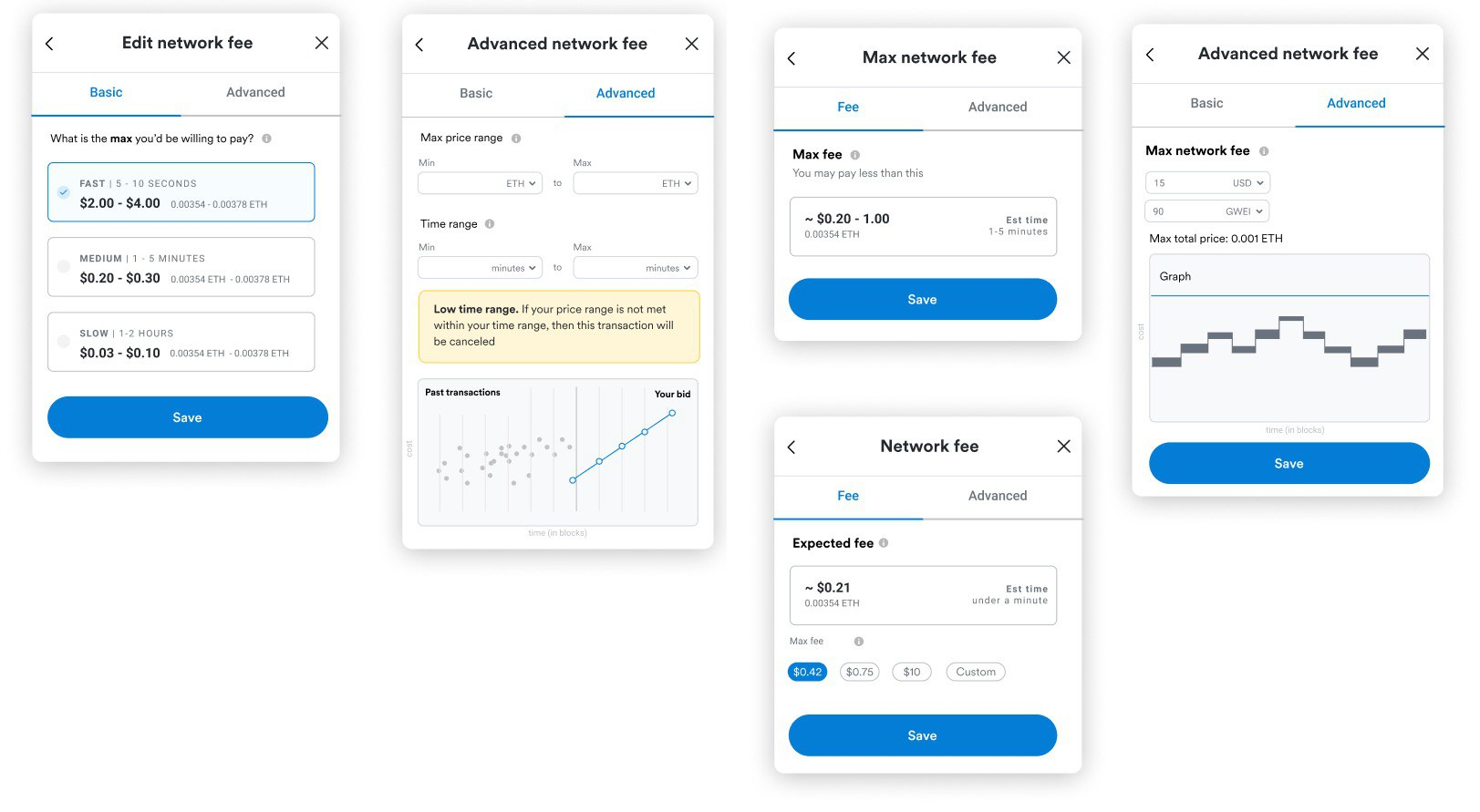

On an EIP1559 implementer’s call, Dan presented mock-ups showing how the various parameters in an wallet would look to a user, highlighting how they can be hidden or exposed depending on the desired level of user intervention.

The designs were intended to be a reference for community discussion, and help us imagine both 1559 and the escalator algorithm from the perspective of a user.

By introducing a reasonable alternative proposal and re-framing developer criticism to prioritize the challenges of users, the EIP 1559 / Escalator discussion has very deftly created new space of exploration toward the end goal of improving the fee market. It’s far from teed up for the next hardfork, but like the big rig in Mad Max, it’s still moving forward.

The future of Ethereum: All shiny and chrome

I believe EIP1559 / Escalator is an important issue for the Ethereum community to watch and learn from, particularly because it has many of the same characteristics as another more distant (and more dramatic) improvement on the Stateless Ethereum horizon: Oil/Karma EVM semantic changes. Just as in the fee market, some of the proposed modifications are going to have significant second-order effects on developers and users. Also as in the case of 1559, there is a clear user experience aspect to rally behind, and thus an opportunity for coordination with developers who understand that experience to help proposals keep momentum toward an eventual successful upgrade.

Improving Ethereum (1.x) and any other public blockchain is an arduous journey. The right route of discussion should be one that keeps meaningful improvements still on the horizon, and moreover ensures that the developers and users most impacted are heard and their concerns incorporated. Because at the end of the day, we’re all riding the same big rig toward the gates of Valhalla… er, Serenity. Staying ahead of the state bloat problem means continuously and constructively proposing, criticizing, and amending changes without losing momentum— our survival depends on it!

Leave a Reply